Key Takeaways

– Testing, treatment, and recovery for COVID-19 patients vary widely across the U.S.

– The pandemic laid bare existing disparities in health care access and treatment.

– While treatment regimens are underway for FDA approval, the best protection against COVID-19 include social distancing, wearing a mask, and quarantining at home.

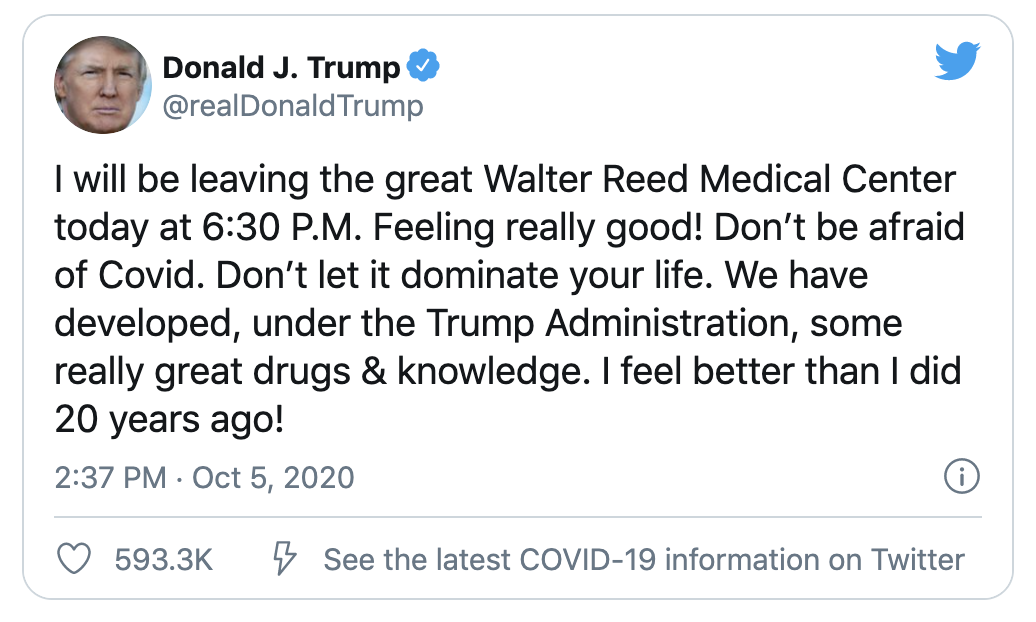

On October 2, about seven months after the start of the pandemic, President Donald Trump announced his COVID-19 diagnosis via Twitter. His subsequent treatment was top tier: around the clock care at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, supplemental oxygen, and experimental drugs unavailable to the general public—a regimen consisting of an antiviral therapy known as remdesivir and Regeneron’s antibody cocktail. The Food and Drug Administration has since approved Remdesivir for the treatment of COVID-19 requiring hospitalizations—becoming the first FDA approved treatment for the virus. 1

The president’s own treatment came in stark contrast to the news emerging from hospitals around the country: overwhelmed hospitals, reused PPE, and patients told to take Tylenol after being turned away from the emergency room. While President Trump received quick and effective treatment, the reality for many in the United States often includes a struggle to stay insured and healthy during the pandemic. Since September 2020, 12.6 million people have been unemployed in the United States, leaving millions uninsured. 2

“If the president is receiving an effective treatment, that is safe, everyone else should be offered the same,” Leo Nissola, MD, an immunotherapy scientist at the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy in San Francisco, tells Verywell.

What This Means For You

With vaccine trials currently in development and treatment regimens inaccessible to the general public, your best defenses against COVID-19 are still social distancing, wearing masks, and quarantining at home.

How COVID-19 is Impacting Americans

Since March, over 222,000 people have died from COVID-19 in the U.S., and over 8 million people have been infected. 3

The virus that quickly ripped through the country, laid bare existing disparities in health care access and treatment.

Symptoms and Testing

Testing is now more widely available in the U.S. than it was at the start of the pandemic. Availability and turnaround for results vary by state and county, but free COVID-19 testing is available for those with and without insurance.

In late April, nearly two months after the start of lockdowns in the U.S., Alicia Martinez, a clerk in Markham, Illinois, started experiencing COVID-19 symptoms. “Monday came and my throat hurt really bad,” Martinez tells Verywell. Coughing, body aches, sneezing, and a fever accompanied her sore throat—all common symptoms of COVID-19. 4

On May 1, Martinez headed to a drive-through COVID-19 testing location. Three days later, she received her results. She tested positive.

According to Julita Mir, MD, practicing infectious disease physician and chief medical officer at Community Care Cooperative, drive-throughs are a common way to get tested. “Drive-throughs are probably the easiest way,” Mir tells Verywell. “You are just in your car and get the testing done.”

What Are Your COVID-19 Testing Options?

Antigen test: a nasal swab test that checks for active virus in the human body

Antibody test: a blood test that checks for the presence of antibodies

PCR test: a nasal swab test that detects RNA from the coronavirus

Quinn Johnson*, a textile designer in New Jersey, showed no symptoms. As a mother of two, Johnson regularly tested bi-weekly because her kids were involved in a pod—a backyard socialization group where a small, self-contained network of parents and children limited their social interaction to one another.

Similarly to Martinez, Johnson also took an antigen test at a Walgreens drive-through in New Jersey on October 2. Within 15 minutes, Johnson received her positive results. “I freaked out,” she tells Verywell. “I immediately made my husband and two kids get tested.”

Early on in the pandemic, this rapid widespread testing was not available. In an effort to conserve testing resources, tests were exclusively available to people showing early symptoms, those at high-risk, and front-line healthcare workers. In July, the FDA authorized its first test for broad-based screening. 5 Over the week of October 19, according to data collected by the COVID Tracking Project, an average of 1,048,000 tests were conducted per day—falling below the current nationwide target of 1.8 million daily tests developed by researchers at the Harvard Global Health Institute. 6 Only 10 states are meeting this target, while five states are close, and 36 states are far below the target. 7

According to Mir, results can take anywhere from two days to one week. “When we were in the peak, May or late April, it was harder to get tests back,” Mir says. “People were waiting a week to get their test results.”

A delay in receiving results, which during peak cases can be reportedly up to 10 days or more, often puts patients in difficult situations. Without test results, many can’t make decisions on whether to change their behavior, miss work, and more.

While medical professionals advise people to act as if they have COVID-19 while waiting for results, that may not be realistic for longer wait times. During September and August waves, the average respondent waited 6.2 days between seeking a test and receiving test results. 8 Average testing times have fallen since, from 4 days in April to 2.7 days in September. But as cases begin to surge once more, this number may fluctuate.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Five days after Martinez tested positive, she fainted and was admitted to the emergency room along with her father at Rush Medical Center in Chicago. “I woke up on the floor and my head was hitting the edge of the door in my bathroom,” she recalls.

Martinez only waited 30 minutes before she was admitted to the hospital. Surprisingly, emergency department wait times decreased by 50% during the pandemic, as many people saw them as highly infectious areas and steered clear. 9

To figure out why Martinez fainted, doctors conducted a chest x-ray, electrocardiogram, and creatine phosphokinase test.

In the early stages of the pandemic, because testing options were limited, doctors relied on other tests to diagnose coronavirus and health issues exacerbated by COVID-19. Daniel Davis, MD, medical director for Knowledge to Practice, tells Verywell doctors often did tests in the chest area because the virus predominantly affects the upper respiratory system.

“The lack of testing was one of the things that made it harder to figure out how to respond to the pandemic,” Davis says. “So early on, we were using secondary indications like chest x-rays or CAT scans of the chest.”

Martinez was discharged that same day with no real explanation for her fainting spell. While her case was less severe, her father’s was not. Prior to Martinez leaving the hospital, her father was admitted to the emergency room. “He needed more oxygen,” she says. He ended up spending a week in the intensive care unit.

Many COVID-19 patients with less severe symptoms report being turned away from hospitals to ride out the virus at home. Martinez was given Tylenol and sent home. This is a typical course of treatment for COVID-19 patients, along with fluids and rest. 10

The government has essentially abandoned its responsibility of caring for people who are getting sick.

— Quinn Johnson, New Jersey- based COVID patient

On a Tuesday, Martinez got a call from the doctor. “I got the call saying that he [her father] wasn’t doing well anymore and his kidneys are starting to fail,” she says. “Pneumonia had come back way worse. On May 28, they’re saying there’s nothing they can do.”

Martinez was frustrated with how the hospital handled her father’s care. “When they wanted to intubate him, they didn’t ask if I wanted to speak with him,” she says. “It was very rushed and it happened so quickly.” Martinez’s father died from COVID-19 soon after.

Financial Impact

Although Martinez was discharged that same day, her hospital visit cost $8,000. Luckily, she was insured and paid a $75 copay. Her father’s hospital bill came in close to a million dollars.

In recent years, the cost of emergency room visits has skyrocketed. In 2018, the average emergency room visit cost was $2,096. 11 High medical care costs and lack of health insurance can prevent people from seeking care. 12

Contracting COVID-19 also posed financial challenges for Johnson. “We had to cancel our backyard pod for two weeks, and still had to pay our babysitter for it,” Johnson says. Because of the pandemic, Johnson has been unemployed for the year. “The pandemic killed me financially because I don’t have time to work with my kids at home,” she says. “My husband was furloughed and then lost his job permanently a couple months ago so we can’t afford childcare.”

In New Jersey, where she lives, the average cost for child care for a 4-year-old costs $10,855 annually, according to the Economic Policy Institute. 13 And according to data from September, women are leaving the workforce at four times the rate of men. 14 Families, and women, in particular, are bearing the brunt of taking care of children and running a household during the pandemic when many children haven’t returned to in-person teaching.

Although Johnson was asymptomatic, the pressures of being uninsured during the pandemic caused her stress. “If we had gotten sick, we would have had to rush to get health insurance or evaluate how much treatment would cost and weigh our options,” she says. A health insurance plan with Cobra Medical Insurance would cost her $3,200 a month.

“The government has essentially abandoned its responsibility of caring for people who are getting sick,” Johnson says. “So many people have lost their jobs, have no income or prospects, and health insurance is still super expensive.”

Recovery

After Martinez was discharged from the emergency room, she spent her time in bed and drank fluids like tea and water. She slowly started feeling better after her visit to the hospital. “I think I was just really dehydrated,” she says. “After I came home, I just started drinking more liquids.”

Although Johnson was asymptomatic, she erred on the side of caution by drinking fluids, resting as much as possible, and taking vitamin C and zinc.

While recovery may look different for everyone, exercise, regular eating, and hydrating often are recommended recovery steps according to Davis. “Once you’re no longer infectious, we really want you to try to get your muscle mass back and get that strength up,” he says. COVID-19 can put a strain on different parts of the body so exercise and eating healthy can help in recovery.

According to data from the Corona Tracker, about 65% of COVID-19 patients in the U.S. recover. But even after testing negative for the virus, thousands of people are now considered “long-haulers,” where they continue to exhibit symptoms and complications from the virus many months later. Published studies and surveys conducted by patient groups indicate that 50% to 80% of patients continue to have symptoms three months after the onset of COVID-19. 15

In the United States, millions remain uninsured and unemployed. With vaccine trials currently in development and treatment regimens inaccessible to the general public, the best defenses for the average American against COVID-19 are still social distancing, wearing masks, and quarantining at home.

*In order to respect their privacy, Quinn Johnson’s name has been changed.