AUTHOR

Yudi Liu

In recent years, Value-based care (VBC) has garnered national attention and investment from stakeholders in the public and private sectors. VBC is a framework for healthcare reform that ties together goals of quality, equity, and cost-of-care to incentivize primary care differently.

Rather than per visit, payments to providers are aligned with patient outcomes and other indicators of quality: limiting unnecessary hospital admission, improving control of chronic diseases, and activating patient engagement, to name a few.

VBC moves away from the traditional fee-for-service (FFS) environment in which providers are rewarded for the volume of visits and instead reimagines care delivery that is coordinated, affordable, and attuned to the whole patient – their physical, behavioral, and social needs.

Healthcare organizations, confronted with growing rates of healthcare spending (18.3% of GDP in 2021) and worsening health system performance, have tried various value-based arrangements to course correct. In 2012, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) pioneered the first Accountable Care Organization (ACO) program to steer provider groups toward care delivery redesign, linking patient health outcomes with care experience and reducing unnecessary costs from care fragmentation.

An ACO is a group of physicians, hospitals, and/or health centers “accountable” for the overall cost and quality outcomes of a defined population. As an ACO, C3 is both a product of, and a vehicle for, value-based transformation. We are driven by the understanding that when a health system is responsible for all the care a population receives (i.e., total cost of care), the system will be pushed to advance care coordination, risk management, and primary care integration, because cost is a matter of sustainability.

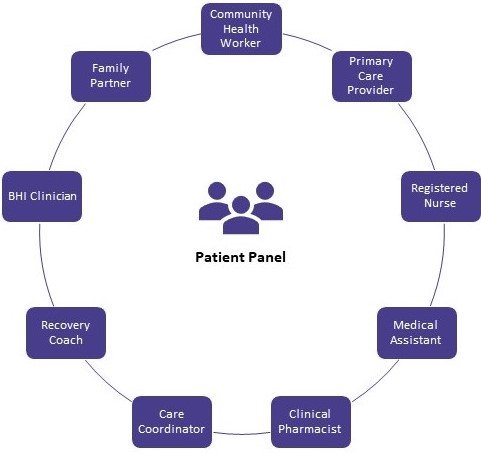

The Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) model is a VBC approach that has dramatically improved primary care capacity and performance, focusing care at the patient level. With an emphasis on multidisciplinary care teams, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, and navigators, who work together to provide coordinated care, the PCMH model supports processes and activities that orient toward patients and their families.

The PCMH model is the backbone on which C3 health centers have spent the past 10-15 years building multidisciplinary care teams, empanelment workflows, and social health partnerships to care for complex populations.

As we have evolved, however, our board of health center leaders have recognized the PCMH model would not be enough to meet the goals of VBC and promote true population health for our community of FQHCs. The organization needed a new framework to spearhead and articulate this transformation away from FFS payment for its FQHCs, who, by nature, are incubators for innovation.

So, we asked ourselves the following: How can the PCMH model evolve to advance VBC in the context of ACOs responsible for TCOC, while at the same time uplift FQHCs and the populations they serve?

The Integrated Primary Care (IPC) model emerged as a blueprint for addressing these challenges and as an organizational reinvestment in VBC at FQHCs. Comprised of seven domains, the IPC model prioritizes health outcomes that impact utilization and finances. Engaged Leadership, Quality Improvement, Patient Centered Access, Behavioral Health Integration, Substance Use Treatment, Addressing Social Drivers of Health, and Trauma Informed Care are the building blocks of the IPC wheel. Health Equity is intentionally not a separate domain, but rather a lens through which all the domains should be implemented and measured.

Back in 2020, C3 formed the primary care capitation (PC Cap) advisory council, represented chiefly by health center leaders and staff, to focus discussions and activate around the design of the IPC model. First, health center CMOs underwent a formal exercise to analyze what was missing from the PCMH model. They decided on the seven IPC domains that are integral to integrated primary care. Subgroups based on expertise and experience formed to address each domain, including crafting outcome measures that would appropriately reflect and ambitiously affect quality. The advisory council conducted a literature review and interviewed subject matter experts to design the primary care team that would deliver the IPC model.

All-purpose and adaptable to adult and pediatric patients, this care team model engenders collective accountability for the whole (population) and the sum of its parts (the individual patient and care team members). In a time when vacancies, retention, and burnout affect the healthcare workforce, it is essential to empower the care team, so that each care team member feels equally valued and supported while caring for the patient.

Complementing our development of the IPC model and ongoing VBC work has been a more favorable policy environment. The Baker-Polito administration increased investments in primary care and behavioral health as well as in market reform and managing its high costs. Similarly, the state’s Medicaid agency, MassHealth, has spent the past few years engaged with stakeholders, including ACOs like C3, CMS, and the Massachusetts Executive Office of Health and Human Services (EOHHS), on designing a more advanced value-based delivery model for its ACO program.

Launched in April 2023 and supported by their CMS 1115 Demonstration Waiver, MassHealth’s “sub-capitation” model pays ACO primary care practices prospectively for their care of beneficiaries. This per-member-per-month (PMPM) reimbursement engages providers in delivering better quality and more flexible care to their patients.

Health centers no longer need to rely on billable visits and their physicians to generate revenue. Rather, staff are empowered to work at the top of their license and to do so together as a care team with the patient. In sub-capitation, because payments are preset, the length and quantity of visits – hallmarks of the FFS grind – are deemphasized. Practices are afforded greater flexibility to tailor care to patient preference, operational capacity, and available resources.

MassHealth’s policy to pay upfront also extends to discretionary funding in which practices, depending on their tier of primary care integration and maturity, receive add-ons to support additional services. Such discretionary funding promotes innovative improvement work like remote patient monitoring, where barriers such as short-term return on investment often prevent adoption.

C3, with over 200,000 MassHealth beneficiaries, always had our finger on the pulse. As MassHealth was developing their proposal to CMS in 2021, we jumped at the opportunity to represent the perspectives of health centers. At listening sessions and directly with MassHealth, we advocated loudly for a payment model that would bring FQHCs’ efforts on sustained team relationships and integrated care services to the fore.

As a result, advocacy and preparedness sprung internally. We adapted NACHC’s Payment Reform Readiness Assessment Tool to evaluate each health center’s “Primary Care Cap Readiness.” The purpose was to uncover where each FQHC stood with regards to the seven IPC domains and three other supporting domains: information technology, population health, and finance. Gap reports were produced from these assessments and shared with health centers. They highlighted strengths and opportunities for the primary care team and processes to support their transformation. Similarly, by achieving clarity on health centers’ present capacities, we knew where and how to prioritize our work with health centers as we prepared for the new waiver and state policies.

Because our health centers share responsibility for the population of enrollees, savings and losses are distributed. This model promotes collectivism, which is also crucial to collaborative growth and sustainability.

Amanda Frank, Vice President of Quality and Innovation, who lent her expertise and knowledge for this post, emphasized how as C3 strives for VBC, system and policy changes must reinforce the identities and impact of FQHCs as safety net providers who have been leading the work in healthcare transformation since the beginning.

We must ask ourselves: What does it mean to design a delivery and payment system that considers the root causes of health disparities? At C3, we believe it is looking to the patients and providers who experience these inequities acutely and leaning on them as the experts.

Ironically, to assert value-based care as a goal for the country’s healthcare system is to risk overlooking the past and current transformation that FQHCs have achieved. Part of developing the IPC model and forthcoming Team-Based Care Toolkit for Integrated Primary Care is to share the impressive work the health centers have accomplished and to recast them as innovative organizations creating their own destiny.